«We’d like you to look nice and toned. You can keep your measurements as they are, we want your hips to stay at a 35. Just firming, and tightening, you know?»

This is a very common refrain from agents. Being «toned» and «fit» have become valuable traits for models in the past five years. Especially in the mid ’00s, a specific thinness was ubiquitous: very thin bodies with seemingly zero body fat or muscle tone. This new «fit» body ideal that was for a long time relegated to catalogue and commercial models, is now an industry-wide standard. It seems that every runway and editorial model has a six pack these days.

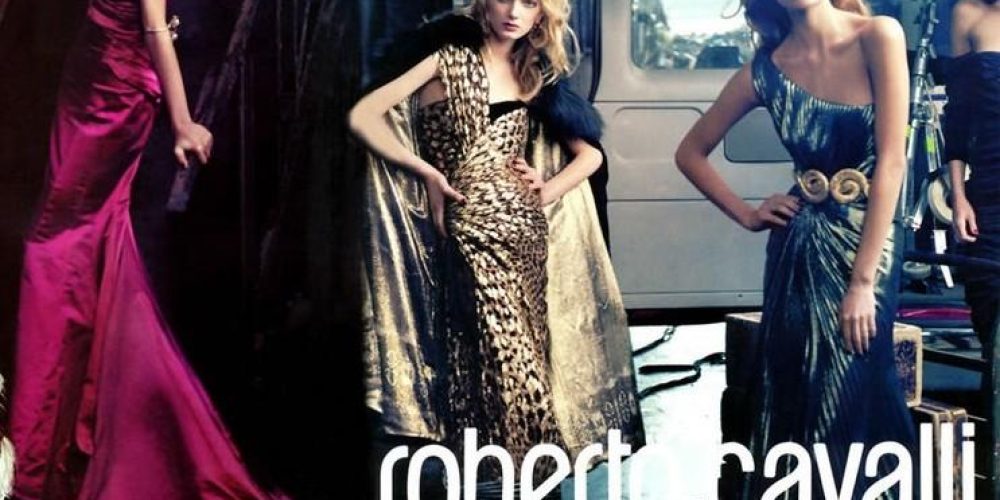

As you can see from this 2005 Roberto Cavalli campaign, the women in these images appear to be standard editorial model size. Their naked body parts appear almost entirely smooth. We see visible collar bones, armpits, shoulder blades, and breast contours, but no muscle striation in their arms, backs, thighs, abdomens, or bums.

Similarly, in this 2008 campaign for Fashion Targets Breast Cancer, there is very little visible musculature. One contour on Daria’s right quad and Lily Cole’s left. Stomachs are flat, but there are no visible abdominal muscles.

Again, in this 2010 Calvin Klein campaign, we only see contours of collar bones, a pectoral muscle, and a calf muscle.

Similar representations of bodies are still easily found in major campaigns and magazine images. But there has been a rise in very specific representations of «fit» bodies, probably in reaction to the public’s expressed dislike of thin bodies that are «too thin» and «unhealthy».

Visible muscularity, usually accompanied by a spray tan on white models, read as «fit» and «healthy» without straying from a standard measurement of 34″-24″-34″.

These images communicate health without extra fleshiness. Indeed, models must have low enough body fat for the contours of muscles to show on camera. This kind of fitness is a lot of work, and requires a lot of time spent exercising to achieve.

Most people cannot attain this specific look for several reasons:

It takes time to workout

Specific kinds of exercise are not enjoyable for all

Individual genetics don’t always support this specific look

Specific diets/supplements/drugs to achieve low body fat require knowledge, money, and a commitment to a specific routine for consumption

Models, like actors and athletes, perform this labour in order to do their actual modelling labour.

Image consumers see thin, fit, muscular women. There is an emphasis on not looking «too» muscular; in shape, but still conforming to a heteronormative femininity.

Coupled with Instagram photos of green juice and yoga poses at sunset, these bodies are read as attainable with the right lifestyle. They’re seen as realistic and attainable because they are not «natural thinness» or «unhealthy starvation» but the fruits of healthy labour. Those abs are status symbols, read as ethical, democratic, and attainable through some hard work.

But it’s Candice Swanepoel’s full-time job to look like Candice Swanepoel — and she’s being paid accordingly.

Most models are not compensated for hours of unpaid «maintenance», but are nevertheless expected to police their diets and exercise diligently to secure their next job in an incredibly competitive industry, not to mention to placate their agency.

Are these images of «fit» women better than images of very thin women? Nope.

They don’t even necessarily portray healthier bodies. No human is perfectly healthy. Even if a body could be perfectly healthy, it may not look like an advertiser’s depiction of fitness. Healthy people come in all shapes and sizes, and so do unhealthy people.

But if consumers look up to models, shouldn’t we be presenting them with the healthiest bodies possible? Won’t those images inspire women and girls to be healthy?

No. The emphasis on conspicuous fitness distracts.

The bodies visible in media should be diverse. A narrow criteria for representation perpetuates the harmful idea that some bodies are shameful and unwelcome. That’s why the ubiquity of thinness in the media is harmful: not because thinness is inherently bad, but because there is an over-represented, specific body type used to advocate that a specific body type should be aspirational at all.

Clockwise: model Ashley Graham via Refiney29; CrossFit athlete Annie Thorisdottir in Vogue by Bruce Weber; actress and writer Lena Dunham in HBO’s Girls; model Lais Ribiero for Gap FW 2010 by Craig McDean

Clockwise: model Ashley Graham via Refiney29; CrossFit athlete Annie Thorisdottir in Vogue by Bruce Weber; actress and writer Lena Dunham in HBO’s Girls; model Lais Ribiero for Gap FW 2010 by Craig McDean

Thin, muscular, and fat. Healthy, and unhealthy. Thin bodies with boney arms and thigh cellulite. Muscular bodies with stretch marks and tummy pudge. Fat bodies, period. Bodies of every colour. Bodies that aren’t photoshopped to the point of marble-like smoothness. Bodies that are gender non-conforming. Bodies with prosthetics and body hair and wrinkles and sagging and scars and pimples.

Some people are thin, some are muscular, some are fat, and some are all of these at once. But no body is normal, and no body is immoral. We all deserve to be represented; we’re all real.