In 20th century American media, African American women were rarely represented in ways that respectfully reflected their diversity of self-identities. Rather images of black women were refracted though white fears, prejudices, and preoccupations with specific ideas of gender, sexuality, and class. The Civil Rights era saw African American consumers and media to express types of beauty distinct from white America, but these gains failed to endure.

The modelling industry in the 21st century is unquestionably dominated by whiteness. Of who I argue are the most successful female models working today, 16.05% are women of colour and, more specifically, 7.41% are of African descent. The modelling industry did not emerge from the Civil Rights era free from mid 20th century ideas of race and gender, but has reverted to those very restrictions that were temporarily loosened in the 1960s-1980s.

In the early 20th century, beauty was depicted as necessarily white in popular American culture and media. (McAndrew, 785) Limited by societal expectations of how to perform gender and class, white women occupied a space in popular culture where they represented socially respectable, admirable qualities. Black women were not afforded such a space. Representations of black women were restricted to “either a hypersexual ‘Jezebel’ or the unattractive house servant.” (McAndrew, 785) In the modelling industry, some black women were able to find work, but only insofar as they could “pass” as white women. (McAndrew, 790) As such, the presence of black women in the media did not challenge the publicly perceived racial reality.

Due to a growing African American middle class following World War Two, advertisers began to target this heretofore “untapped” consumer market through newly established middle class magazines geared specifically towards Black America. (Haidarali, 10) (Leslie, 426) White-owned companies and their advertisers sought to create “black” versions of their regular advertisements. Hair colour company Clairol, for example, would run their regular ad in mainstream media, and an ad for the same product in African American media with a different model and perhaps a different slogan. While wanting to target as many consumers as possible, companies chose not to create one advertisement that would appeal to all audiences, but rather to keep advertisements and audiences segregated.

This top-down response to the growing African American market, dovetailed with a ground-up response; African American entrepreneurs provided black models to fill the new advertising demand for them. As Laila Haidarali traces in her article ‘Polishing Brown Diamonds,’ modelling emerged as a profession for black women in the early postwar years; the first African American modelling agency opened in 1946. (Haidarali, 15) Some successful African American models who had prospered in the era of “passing,” used their expertise to establish modelling agencies to fill the need for black models. (McAndrew, 790)

Along with the financial appeal of owning a business, model-turned-agent Ophelia DeVore operated on a social uplift agenda. Seeking to challenge the “jezebel” and “mammy” stereotypes, DeVore aimed to “popularize a dignified image of black womanhood [and] create an ‘internationally acceptable person of [colour]’.” (McAndrew, 790) As Haidarali writes,

Photographic magazines such as Ebony attempted to overturn the racist stereotyping of African American women as dark-skinned, unattractive mammies, maids, and laundresses by endowing the “Brownskin” with attributes historically denied African American women—beauty, poise, and success. (Haidarali, 13)

In this way, modelling was wielded as soft power.

In this era, several black women found success as models. For example, Helen Williams’ hourly rate ranged from $50 to $100, while the average white model was earning $15. (McAndrew, 791) However, the spaces for the images they represented were largely within Euro-American prescriptions. Haidarali describes the black model ideal as “a heterosexual and feminine creature who was visibly African American and virtuously middle-class.” (Haidarali, 12) While the women in these images appeared attractive and wealthy, they did not “forge a racial identity wholly independent of white America.” (Haidarali, 12)

On top of sexual, gender, and class demands, black models also had physical demands to fulfill, as did and do all professional models. Black models of the 1950s generally had lighter skin and more European-looking features. Michael Leslie writes that black models, “were invariably light complected. Blacks with thick lips, broad noses, dark skin […] were routinely ridiculed and their images excluded from advertising pages.” (Leslie, 426) Leslie notes that there was an increase in images of models with “phenotypically” African facial features and natural hair textures in Ebony magazine during the 1960s and 1970s, and he identifies this as a corporate response to the Civil Rights movement. He notes however that by the 1990s, these gains had “failed to overcome Eurocentric norms.” (Leslie, 433)

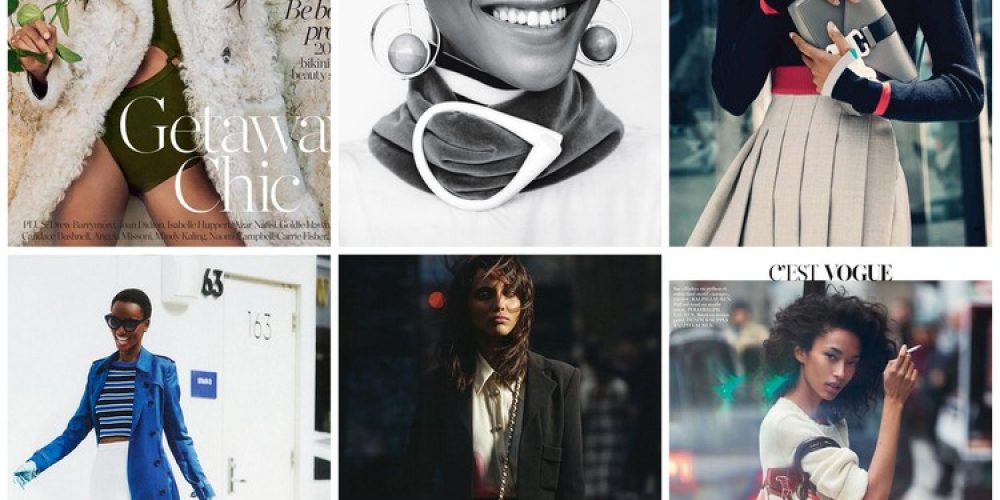

While media geared towards specific racial demographics has not disappeared in the 21st century, the majority of magazines and advertisements have to appeal to a global market in which consumers are not exclusively white. Since the majority of popular media has been integrated, to borrow a Civil Rights term, so too has the modelling industry. Theoretically, the editorial pages of a magazine could be filled with any model, no matter her skin colour, ethnicity, or hair texture. There are no modelling agencies exclusively for African American women, because every agency is integrated. Exceptionally, most East Asian agencies have segregated boards, (see below images). But in most other markets, as workers, models of all skin colours compete for the same jobs.

Furthermore, the fashion and modelling industries have become truly transnational. Although there was exchange in the mid-century between American and European centres of fashion, (McAndrew, 790) the level of transnational business that exists today in the fashion and modelling industries would have been unthinkable at the time of DeVore. A hypothetical model apartment in Tokyo in 2015 houses girls and women from Canada, Germany, Lithuania, Brazil, and Kyrgyzstan. They meet with Japanese casting directors and shoot a Malaysian campaign for a British footwear company. The level of globalization is incredibly intense, yet whiteness still dominates the industry.

Models.com is a popular website that assesses and ranks working models in a variety of categories. Although not assuredly impartial, its rankings are the best available assessments of which women dominate the industry in influence and earnings. The “Money Girls” rankings are comprised of women whose images are regularly consumed by the average person, regardless of the consumer’s interest in fashion. The list consists of the 81 highest-earning female models working today. They have lucrative contracts, and ambassadorships for “power clients.” Models.com explains,

There is an interesting device you can use to get an estimate on a model’s money girl status. You take a list of the highest paying clients in fashion, weigh the going rates these clients pay for their contracts and then apply it against the body of models employed by those clients.

Who are the power clients? They are brands like Victoria’s Secret, cosmetics giants like Estée Lauder & Lancôme, as well as the many fragrance contracts and endorsement deals. Or the rare case of a clothing company (like Calvin Klein) willing to pay a model a high-six figure sum.

The list is divided into three categories: nine «A-listers», 30 «Contract girls», and 42 «High earners». The «A-listers» are the women annually earning six-figure incomes and most have been modelling for over a decade (for example, Gisële Bundchen, Kate Moss, and Natalia Vodianova). «Contract girls» hold at least one high-paying contract with cosmetic, lingerie, or fashion companies. Many have been modelling for 5-10 years, and while some are highly-visible in their work for companies such as Victoria’s Secret, others are better known within the fashion industry (for example, Emily DiDonato, Joan Smalls, and Karlie Kloss). «High earners» are some combination of runway models who’ve booked several high-paying fashion campaigns, regulars for mega-retailer e-commerce and catalogue (such as J. Crew and The Gap), as well as non-contract lingerie and swimwear models (for example, Cameron Russell, Ieva Laguna, and Ming Xi).

Average consumers all around the world see their faces and figures on a regular basis, but they are not necessarily at a level of celebrity-like recognition. As of June 2015, 13 of these 81 women are women of colour and 6 are of African descent. 5 of 42 «High earners», 8 of 30 «Contract girls», and no «A-listers» are women of colour.

Ethnicities of the «Money Girls»

From the immense success of women like Joan Smalls, Jourdan Dunn, and others, it’s evident that consumers respond to images of women of colour. However, the small number of them that have had great success demonstrates that although consumers may see many images of black models, it is more likely to be several images of one model rather than of dozens of models. In an interview with The Edit, American model Chanel Iman described this very phenomenon, “[Jourdan Dunn, Joan Smalls, and I] are very successful in our careers, but because in the fashion industry ‘there’s only one black girl allowed,’ they’ve made us compete to be that one girl.” French model Anais Mali echoed Iman’s experience in an interview with popular blog Into The Gloss, stating “I’m getting good work, I’m happy, but I want to see more black girls.” From the perspective of labour, black models face extreme competition in their industry not only from white models, but from each other.

Much like the mid-century models described by Leslie, black models still have better chances of finding work if they have more European-looking features and lighter skin. In The Colour of Beauty, a 2010 National Film Board documentary about race and modelling in New York City, an agent explained that clients, when they do want to hire a black model, are looking for “white girls dipped in chocolate.” Indeed most of the black models successful enough to be included in the Models.com rankings, have thinner noses, lighter skin, and are invariably photographed with long, straight hair. The labour experience of black models and the consumer experience of viewing images of black models in the 21st century, therefore resembles much more the post-war era than the Civil Rights era.