On May 17th, I met with with Dr. Elspeth Brown to talk about her work as a historian of models in the United States. Professor Brown researches U.S. social and cultural history with a particular focus on the relationship between visual representation and the social construction of race, class, gender, and sex. In 2012, she authored a chapter called “From Artist’s Model to the ‘Natural Girl’: Containing Sexuality in Early-Twentieth-Century Modelling,” in Fashioning Models: Image, Text and Industry, a fascinating scholarly book about how models have become such powerful icons in modern consumer culture.

The Business Model: This chapter emphasizes performance of race, class, and gender. Can you explain what “performance” means in the context of cultural theory?

Elspeth Brown: I use the term ‘performance’ in a way in which is not the way in which most people probably think about performance – a show or a dance, etc. But rather I use the word ‘performance’ as cultural theorists use it. The distinction there is about the ways in which the body itself, in doing the gestures of everyday behaviour, create the reality that we might think exists before the body. [Judith] Butler looks at the performance of gender as a repetition of certain gestures and behaviours, and thus the body produces gender every day. Scholars have made similar arguments about race. We are used to people looking certain ways or doing certain things that we associate with or think of as race. Race is not something that is pre-determined, but it’s a verb – as in one does, or performs, race. [The term performance] is a way of thinking about the relationship between the body and larger social structures that produce hierarchies and culture.

Dr. Brown in her office at the University of Toronto | Jasmine Chorley Foster

Dr. Brown in her office at the University of Toronto | Jasmine Chorley Foster

TBM: So that becomes more visible in a model’s body?

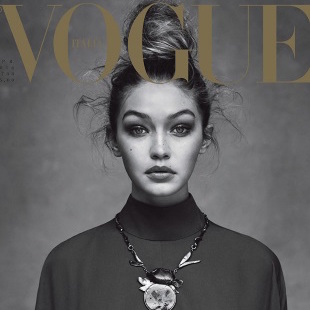

EB: Depending on the historical moment in which the model is working. There are certain sets of assumptions about the meanings of these different looks. In the discourse of advertising for example, the viewers of the model will understand what details in the body are supposed to mean. If we look at an ad in 1941 produced by Edward Steichen and you’re seeing a model who looks Polynesian and she’s wearing a lay around her neck and a grass skirt, there’s all these discourses of colonialism, primitivism, of the woman as nature, of the East, etc. The viewers in 1941 seeing this image thinking of Hawaii and this tropical paradise, come to the ad with those social and cultural assumptions. These assumptions get written onto the model’s body whether or not they’re true. She may not be Polynesian, she may have done the photo shoot on Madison Avenue. We know nothing about her. I use this particular ad to teach students how to analyze images. A model’s lived experience could be very different from what viewers see. The model is meant to be the bearer of all sorts of social meanings and those social meanings are very much determined historically – including the meanings of beauty.

TBM: Can you explain how agents, models, etc. are “cultural brokers?”

EB: Yes, I take the term from the historian William Leach. He looked at the history of department stores, and also the history of the senses and how merchant capitalists produced a new way of looking at shopping that was based upon the notions of desire.

For me, the term ‘cultural brokers’ was helpful to bring into view all the work the goes on in the culture industries that have been historically responsible for bringing together producers and consumers of culture. A broker is the person at the fulcrum of those two groups – art directors, photographers, models, etc.

TBM: Can you explain how the idea of “parasexuality” is present in modelling work?

EB: That term comes from Peter Bailey, who tried to describe a kind of sexual appeal that is a part of modern capitalism and we take for granted in how it’s used to sell products. Bailey calls it parasexuality because he’s talking about female sexuality that’s somehow contained through a mechanism of distance. There’s a solicitation to the viewer of the woman’s sexuality, but the danger of her sexuality is contained by the distancing mechanism.

Female sexuality has historically been seen as dangerous. For long periods of time female sexuality was contained within the home and the family. Women, white women, were constructed as having no sexuality, and to be passionless. But that’s a bourgeois norm. Women who exist outside of the white bourgeois family, have always represented sexuality that is anxiety-producing. So whether we’re talking about African-American female sexuality, or homosexuality, or women working outside the home — maybe in the city working as seamstresses or as models — that notion that women’s sexuality can escape from the controlling mechanisms of the family and marriage, has historically been a source of concern. Parasexuality is one of the ways in which the alluring effects of female sexuality can be deployed as a sales mechanism, but at the same time, is contained. It’s used as a way to spice things up, without causing too much anxiety. The way that female sexuality is contained in modelling is obvious, there’s of course the catwalk and the photograph. This is of course from the perspective of the viewer, outside of the work of the model. Because models are actually touched all the time and historically they’ve had to negotiate that.

TBM: Is the communication of “parasexuality” harmful for image-consumers?

EB: Sometimes I think yes, this harms women. But I also think that people are sophisticated viewers. Some research has been done on young girls and how they’re affected by body image. Historically, I know that has been the case, for example,

TBM: Why was it essential for models to appear upper class in the early 20th century?

EB: It was assumed that advertising was aspirational. Working class people would want to see middle class homes and clothes — which is not so different from today. It was assumed that nobody wanted to see someone who was worse-off than themselves. Then there’s also the fact of who can afford the products. Especially luxury items like fashion.

So for the early 20th century models, they were working class women who thought this was a good option to make a living. But if they opened their mouths and the audience at a presentation heard a Cockney accent, the whole dreamscape would dissolve. Like in Singin’ In The Rain.

TBM: How did models contribute to early 20th century capitalism and consumerism?

EB: It’s their labour as models that sell goods. It’s their job to sell goods by making them desirable. Of course they’re doing this in collaboration with the photographers, art directors, etc. but models work to represent themselves in specific ways. They balance their representations of their selves with the commodity they’re modelling.

TBM: It took a while to convince Madison Avenue that photography was the way to go. In “Rationalizing Consumption” you wrote that a lot of directors and editors thought photography lacked artistry and was too real. How did that change?

EB: Photography itself changed. Photographers became more sophisticated in the way they could capture details of fabrics or jewels and could do it in an artistic way. De Meyer came in and was a magician with lighting. He was able to direct the eye of the consumer to the aspects of the images that were designed to create an allure around a product in the image. Photographers began to convince non-photographers that it could be artistic, and magazine images followed suit.

TBM: In Fashioning Models, you quote Hiller who said, “Fiction and advertising required the subordination of the model’s personality to the narrative.” Does this remain so?

EB: I think the concern was still the same. Most of the time the model is still not named. And historically, models weren’t often thought of as human. They were just machines or vehicles for communicating the look. The best model is the one whose presence with the product is not noticeable. And that waxes and wanes because you have periods where you have Christy Turlington, etc. and it’s usually different with cosmetics. Because that’s co-branding. But Heller was a commercial photographer, who shot things like appliances, or other non-fashion products.

TBM: How did the vocabulary of models’ beauty enforce class and racial hierarchies? Does this continue?

EB: From what I’ve seen, I’m sure it does. But in terms of black modelling, if a model is black she’s more likely to be portrayed as African not African American, and there’s still a narrative of primitivism and exoticism.

TBM: What should a model take away from the early history of the profession? Why should they care?

EB: Because of the reasons we were just talking about. History can help us to understand how social inequalities have played a role in the past and structured negative scenarios for women, and especially women of colour. Learning about that history will help models today understand how they help people see their world. The history in how those images came to be, and models’ roles in them, will help us understand how that imagescape has been created around us. Images carry histories with them, whether or not they’re understood by the maker/reader. In that ‘African Queen’ editorial, for example, just one image can carry the history of colonialism, racism, genocide, etc. despite whatever good intentions of the producers. And photographs are even more powerful because they are often read subconsciously as documentary, and realism.